Women in Mormon History: Emmeline B. Wells

How a feminist pioneer still speaks to our modern Mormon woman experience

In honor of Women’s History Month, I will be doing a mini dive into the lives of women in Mormon history. These will be a mixture of historical information and my own musings. Sources and suggestions for further reading can be found at the end of the post.

Emmeline B. Wells at her writing desk. Image from utahwomenshistory.org

On September 30, 1874, Emmeline B. Wells wrote in her diary: “O if my husband could only love me even a little and not seem so perfectly indifferent to any sensation of the kind, he cannot know the craving of my nature, he is surrounded by love on every side, and I am cast out.” It was only one of many paragraphs over the years lamenting her sadness in polygamy.

However, in public, Emmeline staunchly defended the practice. She wrote, “polygamy gives women the highest opportunities for self-development” and makes “them more truly cultivated in the actual realities of life, more independent in thought and mind, noble and unselfish.” She was only one of many Mormon women who defended plural marriage loudly, but secretly went home and cried herself to sleep over the visceral pain it actually brought her. Perhaps, like historian Benjamin Park suggested, she was honestly just trying to convince herself more than anything.

It’s little wonder we grew up hearing stories of how great polygamy was and never the problems—the women living it themselves kept those struggles buried and hidden away, an unspoken (or sometimes actually spoken) rule to put on a brave face for the sake of the church and then quietly bare the reality of those burdens alone in secret.

Perhaps us modern day Mormon women aren’t so different than our foremothers in this way: defending the priesthood and patriarchal systems that keep us caged, calling it liberation for the camera, convincing ourselves it’s God’s plan we’re pushed aside, stepped on, and abused. Sometimes we can’t even allow ourselves to name the oppressor for fear of jostling the tightrope of faithful loyalty to the church pulled taunt in our minds.

One of the things I love most about studying the life of Emmeline is how much I can relate to her. Perhaps you will too, whether raised in the Mormon community or not. Hers is a story of bravery, resilience, complexity, and contradiction.

Emmeline B. Wells, suffragist, feminist, writer, mother, and plural wife. Image from the Church News.

Emmeline Blanche Woodward was born in 1828 in Massachusetts. Along with her family, she joined the Mormon church in 1842. She soon fell in love and married at 15 to another teen named James Harris.

Though young and filled with romantic notions, her story sadly turned to tragedy. After settling in Nauvoo with her husband and in-laws, she gave birth to her first child, who died after only six weeks. Her beloved husband then left to find work as a sailor and support them. She never heard from him again.

(Forty-eight years later living in Utah, she received a package filled with letters. They were all her letters from James that she never received; letters filled with longing, emotion, and promise. Her mother-in-law had intentionally hid them from her and they were eventually unearthed by a cousin. One can only imagine the heartbreak and devastation at such a discovery. Years later on a trip back East, an eyewitness reported Emmeline visiting her ex-mother-in-law’s grave and calling down a curse upon her. No doubt she was justified in it.)

Emmeline taught school to support herself and in 1845 became one of Newel K. Whitney’s plural wives. He was a 50 and she, 17. It seems their union at first was more of a means for protection rather than a romantic one. Eventually though, she became a true wife and she gave birth to two children in 1848 and 1850. Emmeline later wrote in her diary of her great love and respect for Newel, who was “more than a father” to her; “I looked to him almost as if he had been a God.” (Sept 23, 1874)

Newel died shortly after the birth of their second daughter and Emmeline was now a widow, twice-over, by age 22. She provided for herself and her daughters by teaching again. She would continue to financially support herself throughout her life.

Emmeline pictured with suffragist leaders of the time. Image from fromthedesk.org

Not wishing to live life alone and knowing that a man brought security, Emmeline sought out and proposed to Daniel Wells. She became his fourth plural wife. Though the marriage brought her three more children, their relationship was distant. She even lived separately from the rest of Daniel’s wives and family, and continued to have to support herself.

She then wrote, “I am determined to train my girls to habits of independence so that they never need to trust blindly but understand for themselves and have sufficient energy of purpose to carry out plans for their own welfare and happiness.”

Even now in 2024, I want to have that posted on my wall to remind me to teach this to my own daughters. I wish I’d heard that quote over the pulpit a million times growing up instead of Brother Benson’s “women belong at home” propaganda. How many Mormon housewives left in abusive situations, or just plain left, would have benefited from such lessons? What different choices would woman make for their lives, careers, relationships, childbearing, if they were actually told to prioritize their own independent selves and happiness? How would women in the church fare differently if we’d been raised on the real lessons of our foremothers, instead of the overly-sanitized, male-dominated and mansplained version? Once again, I mourn for us and what we’ve lost as Mormon women from patriarchy.

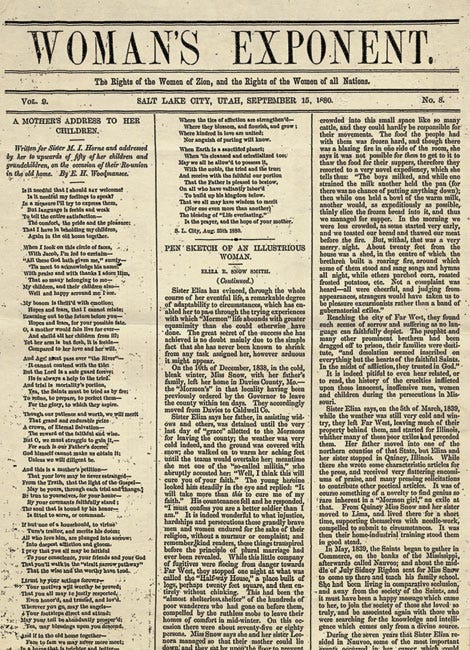

1880 edition of the Women’s Exponent, a feminist periodical created by members of the Relief Society. Image from Wikipedia.

Emmeline began working on the Women’s Exponent in the 1870s, a periodical published by women of the Relief Society advocating for economic, educational, and voting rights. “I desire to do all in my power to help elevate the condition of my people, especially women,” she wrote, and to “better her condition mentally, morally, spiritually, temporally.”

She was a suffragist, but also worked to raise the age of consent for women, lobbied for women’s rights to own property, and fought for women’s ability to hold public offices.

Emmeline dedicated much of her work to women’s suffrage, working with well-known activists such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She wrote continuously of the need for women to gain all rights of citizenship and not to be defined as only wife and mother. In 1870, Utah became the second territory to give women the right to vote shortly after Wyoming, but Mormon women were the first to actually casts ballots and exercise that right in the nation.

It should be noted that the federal government granted this in large part due to their fight against polygamy. The reasoning was simple—give Mormon women the right to vote and they will vote against church leaders and polygamy. However in reality, the opposite happened. Mormon women were just as staunch defenders of polygamy as Mormon men in the public sphere. This included Emmeline.

Emmeline, like many others, lived a life caught in this kind of dual thinking and seeming contradiction. By day, she used her right to vote to support patriarchal structures. By night, she wrote in her diary of struggles, longings, and heartbreaks brought on my being a Mormon woman.

Here again, I see myself in Emmeline. I recall myself as a child standing up in front of my primary class and proudly declaring that I didn’t need the priesthood because one day I would be a mother, even as the words tasted bitter in my own mouth. I can hear my younger self telling my daughter she isn’t allowed to pass the sacrament because that’s just how it is, even as I die a little inside every time I take the tray from an 11 year old boy who holds more authority in the church as a child than I ever will in my entire lifetime. How do we hold these contradictions, these unspoken pains inside us, just for the approval and minimal power that the patriarchal structure grants us if we fall in line? I don’t know. I don’t think Emmeline knew either.

Perhaps if we were allowed to make Relief Society manuals without men’s approval, ones that told the true, full story of our Mormon foremothers, we’d be able as a collective womanhood to sit with those feelings and discomfort to sort through them. Perhaps we’d even be spurned to true action and desire for change. But men have denied us that privilege. They’ve correlated our few scraps of independence to death.

At this point in my life, I’d like to smash it all to pieces, stop begging for scraps from the men’s table, and simply build a better table that fits us all. I like to believe, based on her prolific writings, that Emmeline in her own way had similar thoughts. She wrote and worked for a better world for women. And so, I do the same.

Artistic depiction of Emmeline by Better Days. Image from utahwomenshistory.org

Emmeline wrote in the Exponent that women’s capacities were equal to those of men and should take equal part in the “work of the world.” She urged her readers to be more than “toy” or “household deity” but a “joint-partner in the domestic firm” to comprehend that “in marriage there is a higher purpose than being a man’s pet or housekeeper.” She was determined for men and women to work together equally in the home and outside it as true partners.

Like Emmeline, I tire of being treated as this mythical bastion of femininity in the soothing platitudes and thank-a-monies over the pulpit by (well-meaning but misguided) men. I’m glad you appreciate what I do for you, brother, but instead of putting me on a pedestal and calling that liberation, give me true equality and equity. Work in the trenches alongside me, equally dividing jobs and resources. Let me have the same opportunities you do in the church and at home. Give me true leadership positions that aren’t overseen or granted permission by a man. Stop using “preside” as the language of our marriage covenant. Don’t pull the “priesthood card” and trump me when we disagree. Recognize that we have the same roles: parent and spouse, leader and community member.

In 1910, Emmeline was called to serve at the Relief Society General President. She led the Relief Society in involvement with other national and international women’s groups. She saw the Relief Society as a feminist organization, destined to usher in a new age for women, including universal suffrage and emancipation for women.

What would our lives be like if the Relief Society had been allowed to remain an independent organization, not under the rule of priesthood men? Would we have magazines of feminist writing? Would we work together with other women around the world to not only help the poor and the suffering, but to liberate women from whatever injustices bind them? Again, I mourn for what we lost, the possibilities that were stolen from our grip by men.

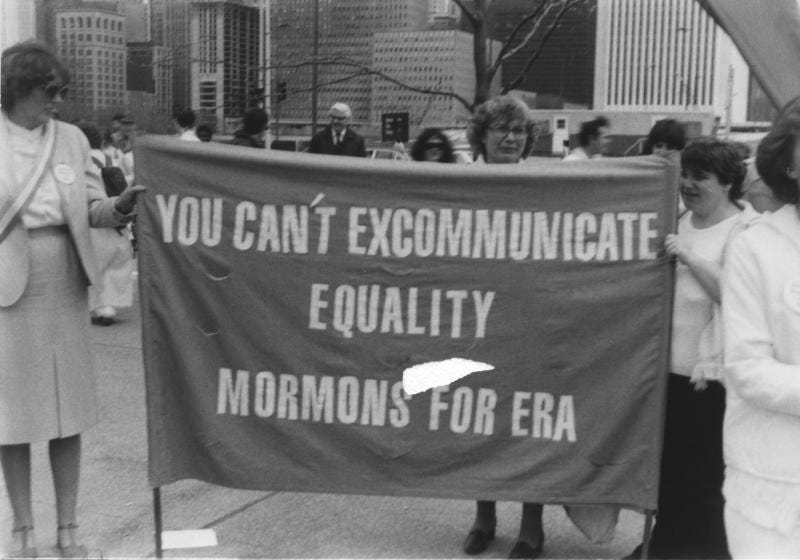

I think of the Relief Society in the 1970s being called on by the church to stand against the Equal Rights Amendment, weaponizing the organization as a bludgeon against its own members’ rights and betterment. I think of the women who were successfully manipulated into actively using their time, talents, and energy to work against progress for their own sex. I think of the women who dared to stand in defiance of the church’s orders and supported the ERA, and the fallout they faced for their disobedience. Emmeline and our foremothers surely wept over us in heaven as this played out; their beautiful women’s organization turned against itself and its original feminist aims.

Mormon women supporting the ERA. Image from patheos.

Emmeline died in 1921 at the age of 93. She was the second woman to receive the honor of having her funeral in the Salt Lake Tabernacle and was buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery.

Mormon women today know little of her. She’s quoted a few times in church publications and mentioned in some manuals. She’s listed as a Relief Society president. But we don’t speak of her feminist writings, of her battle for women’s suffrage, of her tragic sorrows in polygamy. She wrote and wrote and wrote for women’s equality and improvement. She worked alongside some of the biggest names in feminist history, but we never speak her name.

Emmeline is one of my heroes. If I could, I would run into the church office building and demand that she be given more in our curriculum, more in our history, more in our collective Mormon conscious. Not just the faith-filled, but the hard-working, feminist Emmeline, with all her scars and warts.

Now in 2024, over a hundred years after her death, I wonder how much has truly changed for Mormon women since Emmeline’s lifetime. Changes have been made, attitudes shifted, but still, at the core of it all, the church’s foundation is fundamentally unequal. It’s sexism pervades through all its layers. It lives in its doctrine, its policies, and its culture, both in subtle and glaring ways. Relief Society women have morphed—thanks in large part to the hands of priesthood men—from the women who wrote the Exponent and fought for suffrage, to women who fought against the ERA and can’t hold a meeting without the permission and presence of a priesthood man.

I wonder what Emmeline would think of us. Would she think the times haven’t changed all that much, and ask “where are all the beloved, independent sisters I fought so hard for?”

Sources & suggestions for further reading:

“Emmeline B. Wells: Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” by Carol Cornwall Madsen

Pioneering the Vote by Neylan McBaine

American Zion by Benjamin Park

you always get my live reaction commentary but this one broke me